The oldest building on the University of Maine campus is scheduled for demolition this spring. Crossland Hall was built prior to UMaine’s founding and was part of one of the farms purchased for the campus. It currently houses the Franco-American Centre and students have led the charge in an attempt to halt the demolition.

Advocates for preservation highlight the historic value of the building.

“It is the oldest building on campus and pre-dates the founding of the university by over three decades,” said Liam Riordan, the Department Chair of UMaine’s history department. “It has been used for many purposes over nearly two centuries, has been moved to different locations before and the building itself tells a story of our past and its changes over time.”

Lincoln Tiner, a UMaine graduate student, has been helping lead the charge to preserve the building. He has been expanding research into the building’s history and has been working to raise awareness about how entwined Crossland Hall is with UMaine’s history.

Tiner’s research tracks the building’s many uses over the years, from housing university presidents, a fraternity, an infirmary and finally the Franco-American Centre. The building has been changed quite a bit, but its history is more than the sum of its parts.

Tiner also worked in collaboration with others to create a petition to ‘Save Crossland Hall at UMaine’. The petition asks for signatures to show UMaine administrators that people view the building as a pillar of the community that should not be destroyed. Since the petition’s launch on Oct. 20, 1,509 concerned community members have signed.

A question that has been surrounding the debate on Crossland Hall’s demolition is the level of consideration it deserves as a historical building. Crossland Hall has been identified in Save Crossland Hall posters as a Tier One historical building. But what does that designation actually mean?

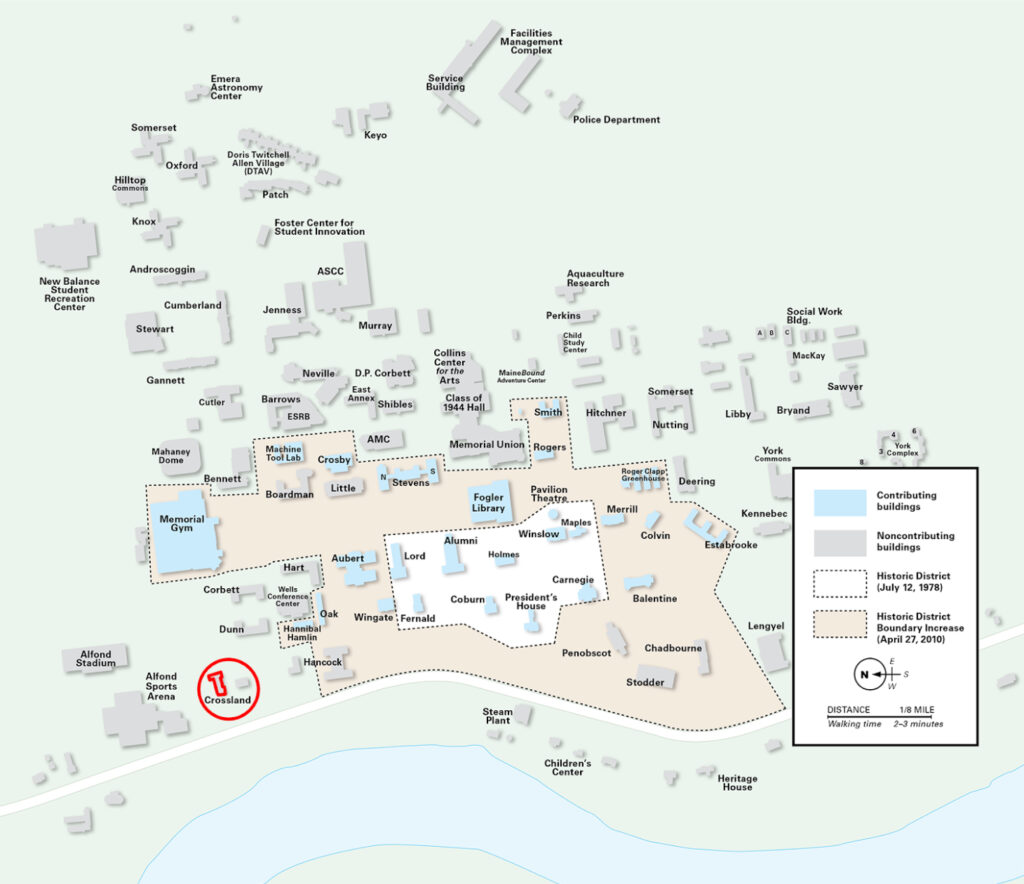

UMaine has a spot on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) as a historical district. The university first received this recognition in 1978, and the historical district was expanded in 2010 adding a number of new buildings to the list of contributing historical buildings.

However, Crossland Hall has never been a part of the UMaine Historical District. So where does this “Tier One” designation come from?

Tier One Buildings were identified in the University of Maine’s Historic Preservation Plan, which was written in 2007. The Tier One category are buildings “considered at present to have the highest level of historic and architectural significance,” to UMaine and consists of buildings built from 1833 to 1909. The plan was put in place after UMaine received a grant from the Getty Grant Program’s Campus Heritage Initiative.

The Historic Preservation Plan placed Crossland Hall on Tier One in recognition of its historical importance and status as “threatened.” The Preservation Plan suggested adding Crossland Hall alongside the other buildings in the application. The building was determined unable to be part of the NRHP due to the extensive alterations that had already occurred both inside and outside the building. The 2008 to 2009 Master Plan does not list Crossland Hall in either Tier One Building list, but does reference it as a Tier One building creating some confusion about its status.

Tiner expressed frustration with the way the university has treated the need for repairs.

“It’s common sense to do timely oil changes for your car to make it last, rather than neglecting it, forcing the engine to blow and having to buy a brand-new car. That’s not only the right thing to do for your car, but also your wallet.”

He believes that the university has been more focused on investments in new buildings than in the maintenance of existing buildings, and that their treatment of historic buildings has been “antithetical to our commitment to sustainability.”

Preservationists have also been fighting to find alternate solutions.

“I hope that a path forward can be found that does not lead to the demolition of this irreplaceable record of the agricultural origins of our land grant university,” said Riordan. One suggestion from students has been to move the building as was suggested in the UMaine 2008 to 2009 Master Plan.

A Crossland Hall Removal Fact Sheet website created by the Office of Facilities Management shares that “the building was deemed unsuitable for renovation in a 2008 campus master plan. Rather than invest money into this aging and inaccessible facility, UMaine will provide the Centre with a more modern, renovated space by relocating them.” It also states that “A historical review determined the demolition does not affect protected historic properties.”

According to the website, in 2025 the Maine Historic Preservation Commission determined demolition would not affect protected historic properties under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act.

Jeff Benjamin, an archaeologist who teaches at UMaine as an adjunct lecturer in the anthropology department, spoke about the preservation of historic buildings. He highlighted the importance of this process remaining a dialogue between both sides of the issue.

Despite the fight to save Crossland Hall continuing, Benjamin considered the preservationist worst case scenario. What to do if Crossland Hall is closed? How is this building’s significance going to be recorded?

“Archaeology does have a very important role to play in documenting a structure like Crossland Hall if it does get torn down,” said Benjamin. “As archaeologists, digging is just one of the very few things that we do, it’s just one thing. We also are keen to document and preserve historic sites and historic structures that are removed for whatever reason.” He added that even if the building doesn’t remain, it is integral for the historical preservation to find ways of preserving Crossland Hall in the university’s memory.

Riordan talked about how the culture around preservation can shift following the loss of historic buildings, heightening public interest in historic preservation.

“Historic preservation commitments often surge in the wake of the loss of a unique structure,” said Riordan, “It would be a shame if a renewed commitment to the long history of UMaine’s built environment only occurred only after an act of destruction.”