University of Maine’s beloved Bananas T. Bear was not always a person in a suit. The first mascot was a living, breathing black bear gifted to the university’s football team in 1914. From then on, a tradition that involved the lives of more than 16 black bears in a 51-year period was born.

In “The History of the Maine Blackbear,” the Sigma Xi chapter of Alpha Phi Omega documented the chronicles of the living mascots. These archives highlighted the loose whereabouts of the bears as well as indicating possible mistreatment. The Beta Theta Pi fraternity, who took responsibility for Bananas for many years, reportedly kept the bears in a pump house on campus for hibernation. This pump house was the main livelihood site and plot of interest amongst local historians. This piece of UMaine’s history ended after the state outlawed live animal mascots in 1966. Old photos and university lore have become the legacy of the many bear mascots that once lived on campus, or so many thought.

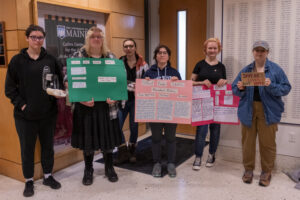

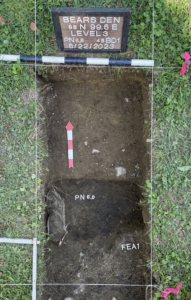

From Aug. 21 to 25, 2023, an interdisciplinary collaboration at UMaine took up an excavation to find the documented pump house/ “bears den” on campus. This archaeological dig began as an exploratory work to add to undergraduate students’ research learning experience (RLE) curriculum. In under a week of digging, however, the finds provided a glimpse into the worlds of the original Bananas. With leadership from Professor Daniel Sandweiss and Hudson Museum Director Gretchen Faulkner, help from assorted faculty, and a more than 10-person excavation crew, Ph.D. candidates Emily Blackwood and Elizabeth Leclerc sat down to discuss their bearings operation. They used the documents in the university archives to generate questions and goals for the excavation.

“From that historical record, we identified some research questions, things that were not documented that well, or things that we wanted to know more about that archaeology can tell us. A lot of the bears only lived for a year or two while they were mascots,” Leclerc stated. “We know anecdotally that the fraternity was feeding them food scraps, leftovers, and at least several of the bears died from food poisoning. We were hoping to identify food remains so we can see in better detail what kind of things the bears were being fed, what their diets were, and how they were being taken care of.”

Those research questions came to a head with various complications during the excavation, stemming from Maine’s climate. Preservation of organic materials relies on unchanging cold, arid or waterlogged conditions. Maine can be notoriously humid and fluctuates in its temperatures. Moreover, the soil here is acidic and ill-suited for preserving remnants of the past.

The pump house’s earliest map was from 1890 but disappeared in the early 1930s. While this timeline indicates the bears’ den are from recent history, Maine soil and conditions leave the site’s integrity in danger of decomposition. During the excavation, the team discovered glass bottles, shards of window panes, coal and slag, pieces of plates from the 1800s and the believed edges of the pump house foundation on the property line. Other artifacts, such as the rubber sole of a shoe, an Edison light bulb and small bone fragment particles (unidentifiable to species), all of which were subject to decay, were found.

“Maine’s soils are very acidic, so they are not the best for preservation. All those little pieces of bone, they may have been too small to identify anyway, but they are also extremely fragile because of the soil. We are talking about just over 100 years. Even over that time frame, the bones do not preserve, and they degrade really quickly,” said Leclerc.

While not the most productive for archaeologists, this climate still yielded interesting findings, particularly an overabundance of slag in the dig area. This slag, a by-product of smelting coal, produced a stratigraphic layer of black, hard-to-dig material sludge. While it is still unclear whether it was the original place where the slag was created, the pump house may have gotten so hot at some points that the slag was formed.

Additionally, the excavation team believed they had recovered a piece of bone resembling a bear’s metatarsal bone. However, inspection by the Hudson Museum’s faunal expert, Sky Heller, proved it was a piece of slag that looked like a bone. While this was a slight disappointment, the site still produced valuable information that contributes to the overall narrative of what was going on at the site. It was determined to be nothing more than bone-shaped slag. The excavated area is rich with the possibility of more findings.

This excavation is likely to become a yearly event as the archaeologists are eager to continue uncovering a piece of UMaine history. This project was developed as an opportunity for RLE students interested in undertaking an interdisciplinary approach to archaeological excavation.

The findings in just a few days in August 2023 are promising. The outer foundation of the pump house has been pinpointed after decades of uncertainty, historical artifacts were found, and remnants of bone have been uncovered. While certain contexts are still sought out, UMaine, unlike ever before, can take a materialized view of our past.