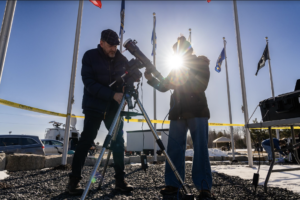

University of Maine Ph.D. student and teaching assistant Nikita Saini participated in a Citizen Science Project collecting solar eclipse data on April 8, alongside her colleague Shawn Laatsch, director of the Versant Power Astronomy Center and Jordan Planetarium.

The 2024 Continental-America Telescopic Eclipse Experiment, otherwise known as CATE2024, is funded by NASA and NSF and comprises 35 teams across the U.S. Each group of two or three individuals was stationed at a location with totality during the eclipse to record film to see how the sun’s corona changes over time and create a 3D view of its corona from 2D pictures.

This year, totality was expected to last approximately one hour between Texas and Maine. The objective of the project is to combine the totality footage taken by each team into a 60-minute movie that reveals the evolution of the sun’s corona and atmosphere.

Saini’s team was stationed in Jackman at Site 33 of 35. This particular location was the best place in Maine to view totality because it lasted three minutes and 29 seconds, which is the most amount of time in the state. They collected three minutes and 25 seconds of data.

CATE was executed in 2017 when the last eclipse to hit the U.S. occurred. Identical equipment and telescopes were placed all along the path of totality and each station collected data one after the other as totality passed over the areas, providing a precise estimate of how the sun’s atmosphere evolves.

Saini and Laatsch traveled to Australia in 2023 when the project started and practiced with similar equipment. By doing dry runs of data collection, they became proficient in training others and knew what to expect. Minor equipment changes since last April 20, including the camera type, extender pieces, and extra accessories, updated the telescope’s view.

Regarding the Site 33 team, Laatsch was the regional coordinator for the Northeast, who recruited teams in New York, Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine. He sought out people who were especially passionate about getting into research and astronomy with a willingness to receive telescope training. Saini, the lead trainer, instructed all Northeastern participants on telescope fundamentals.

Following the eclipse, all equipment used for the project belongs to team members. Since Saini and Laatsch represented the planetarium in their participation, UMaine now has access to the fully-equipped telescope for data collection and teaching purposes. According to Saini, it can achieve night sky observation or solar viewing and take science images or astrophotography pictures. The Camera is a separate and small cube screwed onto the back of the telescope.

“The camera is special in the way that its pixels are tilted in different polarization angles. Which means that the light coming from the sun, those pixels will only detect the light at certain angles,” said Saini. “Because sunlight is going in each direction, those pixels will make sure only light at certain angles enters. That way, we can get an idea of which exact direction the light was coming from and what part of the sun.”

Creating a 60-minute-long movie with contributions from every station was weather permitting. Saini completed the upload of her team’s data to Google Drive on April 11 and is already showing some of the raw images taken.

“Some of the stations got clouded out. As it turned out, weather in the Northeast was the best on Earth, and that was opposed to everything weather models know. Weather is never good in April here,” said Saini. “I heard some of the Texas stations got clear skies just when totality hit, so the clouds parted away. It’s been known to happen. As the winds pick up near totality and the temperature drops, some of the clouds part away.”

The data provides an idea of the start of solar flares and the sun’s activity cycle, specifically how much more active the sun is amidst solar flare eruptions. They were able to calculate how fast the solar flare was moving when it started off the surface of the sun from the pictures.

One aspect that can be studied using the polarization data the team took is which exact direction the solar flare is moving in. A 2D picture limits the amount of information, but by learning which angle it was, astronomers can determine whether it is pointed at Earth or alert satellites.

“We can prepare better or maybe let the satellites know if they want to be out of the way,” said Saini. “If it’s a huge solar flare and it comes at us, it can knock down our satellites, it can affect astronauts that are out in space. If it is even strong, it can knock down the communication system on Earth as well. So, we really want to be prepared for huge solar flares. But, they happen a lot, they keep happening.”

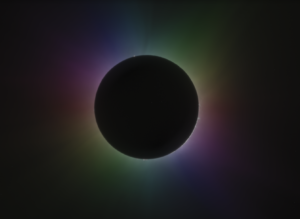

One of the primary science objectives is to learn more about the sun’s corona. Solar physicists do not have extensive information because it is not seen very often. The corona is seen more clearly during a solar eclipse. Most times, data is not as clean.

Coronagraphs can be circular in size and designed to block the sun. However, it can be difficult to get the exact size and distance from a telescope in ground-based observing. The same applies to space-based observing because astronauts are still at a great distance from the sun.

“There’s a huge structure to it, and during solar flares, it can be much hotter than the core of the sun, which is usually the hottest part. So, just learning about what is happening over there because it affects us in some ways is the aim here,” Saini said.

While the coronagraph has several applications in sun observation, it cuts off certain parts of the corona. There needs to be complete precision in the amount of sunlight being blocked. If too much is blocked, astronomers can only see the outer portion of the corona, and if it is not blocked enough, too much sunlight can creep in and affect the results.

“The problem with that is, if you’re making artificial corona graphs or something to block the sunlight, it’s really hard to get the size right, the angular size that is perfectly able to block the sun. The moon is perfectly able,” said Saini. “Every time during a total solar eclipse, the moon is perfectly able to completely block out the sun. It will reveal the whole corona then too.”

Eclipses provide the perfect setting for data collection. Observations can be scheduled in accordance with each time domain of the natural phenomenon. Viewing the eclipse for about three or four minutes from one side does not provide enough information. CATE2024 combined the data, allowing for insight into what was happening on the surface of the sun throughout an hour.

Another team, stationed outside of Millinocket, was led by Kyle Leathers, a high school history teacher who invited his students to come along and participate. He applied, intending to perform it with students.

“It was nice to see because he understood that this is something kids should experience. You don’t know who gets inspired and who chooses that path after it because they’ve got that in,” said Saini.

Pedro Vazquez works for the South Portland Human Rights Commission and led a team near Houlton. While education can be biased and less accessible for people of color, his group was diverse and also involved children. Different backgrounds were crucial to CATE2024 because the project provides opportunities for people that may not be otherwise possible.

Laasch used his connection to the community to recruit individuals and put an application form online. He worked to find who this would benefit, specifically active members of the community to ensure that the equipment ends up in good hands.